To adequately understand the impact of sedation medications during procedural sedation, a sedationist must first understand important aspects of normal pediatric airway and respiratory anatomy and physiology.

The upper airway is composed of three segments:

- Supraglottic — the most poorly supported segment, consisting primarily of the pharynx

- Glottic (larynx) — comprising the vocal cords, subglottic area, and cervical trachea

- Intrathoracic – consisting of the thoracic trachea and bronchi

There are several developmental characteristics that distinguish the pediatric airway from the adult airway:

- The pediatric airway is smaller in diameter and shorter in length than the adult’s.

- The young child’s tongue is relatively larger in the oropharynx than the adult’s.

- The larynx in infants and young children is located more anteriorly compared with the adult’s.

- The epiglottis in infants and young children is relatively long, floppy, and narrow.

- In children younger than 10 years of age, the narrowest portion of the airway is below the glottis at the level of the cricoid cartilage.

Consequently, the small caliber of the pediatric upper airway, the relatively larger tongue, and the “floppy” and relatively long epiglottis predispose young children to airway obstruction during sedation. In addition, the large occiput of the infant places the head and neck in the flexed position when the patient is placed recumbent, further exacerbating airway obstruction.

During normal inspiration, negative intrapleural pressure generated in the thorax creates a pressure gradient from the mouth to the airways, resulting in airflow into the lungs. Extrathoracic airway caliber decreases during inhalation, whereas intrathoracic airway diameter tends to increase. Under normal conditions, changes in airway caliber during respiration are clinically insignificant. However, significant narrowing of the upper airway increases airway resistance, and a higher pressure gradient across the airway is required if minute ventilation is to be maintained. A greater pressure gradient generated across the airway accentuates the normal inspiratory and expiratory effects on the airway. Consequently, the greater negative pressure generated in the pharynx during inspiration tends to further collapse the upper airway.

Resistance across the airway under laminar flow conditions is directly related to the length of the tube and the viscosity of the gas and indirectly related to the fourth power of the radius. Thus, airway resistance is primarily influenced by the diameter of the airway. In addition, the relationship between the pressure gradient across the airway and the subsequent flow rate generated is influenced greatly by the nature of the flow (laminar versus turbulent). Laminar flow is inaudible and streamlined, typically through straight, unbranching tubes. The flow rate under laminar flow conditions is directly related to the pressure gradient (driving pressure). Conversely, turbulent flow is audible and disorganized, through branched or irregular tubes. Turbulent flow (e.g., stridor) tends to occur with high flow rates and often under conditions of airway narrowing and high resistance. A greater pressure gradient is required to move air through a tube under turbulent flow conditions.

Sedation & Respiratory Depression

All sedative drugs suppress the central nervous system in a dose-dependent manner. Typically this is accompanied by a reduction in CO2 responsiveness in the medullary respiratory center. Loss of airway control and respiratory depression are the most common serious adverse effects associated with sedative drug administration. The greater the degree of sedation, the greater the degree of respiratory depression. Respiratory depression increases when combining sedative drugs or when using large doses of a single drug.

Airway Control

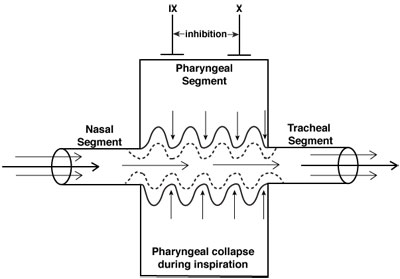

Neuromuscular control of the upper airway (CN IX and X) is inhibited to a greater degree than diaphragmatic activity (phrenic nerve) during sedation/anesthesia. Thus, the negative inspiratory pressures that develop with diaphragmatic contraction may reduce the diameter of the pharynx, a collapsible segment between two relatively well-supported structures, the nasal passage and the trachea. These areas typically involve narrowing of the anterior-posterior distance between the posterior pharynx and the soft palate, epiglottis, and, to a lesser degree, the base of the tongue. Consequently, the pharyngeal segment functions as a Starling resistor, a collapsible tube whose caliber is influenced by pressures within the lumen of the airway and soft tissue.

Airway obstruction during moderate or deep sedation occurs in the supraglottic structures due primarily to the soft palate and epiglottis falling back to the posterior pharynx. While it was previously thought that the base of the tongue was the primary cause of upper airway obstruction during unconsciousness, MRI studies of the airway in sedated children demonstrate that the soft palate and epiglottis are the most likely structures causing the obstruction.

The keys to appropriately managing the pediatric airway during sedation are proper airway positioning and application of positive pressure ventilation when required. Routine management of the pediatric airway includes placement of the patient’s neck in the sniffing position, often with a rolled towel placed underneath the shoulders and administration of “blow-by” oxygen. If obstruction persists despite these maneuvers, the patient’s airway should be repositioned and a chin lift performed to move the supraglottic soft tissue structures, primarily soft palate and epiglottis, anteriorly and away from the posterior pharynx. If a simple chin lift fails to relieve the obstruction, this should be followed by a jaw thrust and application of positive pressure through a flow-inflating anesthesia bag and mask. Failure to relieve the obstruction following application of positive pressure (PEEP) requires positive pressure ventilation with cricoid pressure and endotracheal intubation when necessary.

Ventilation Control

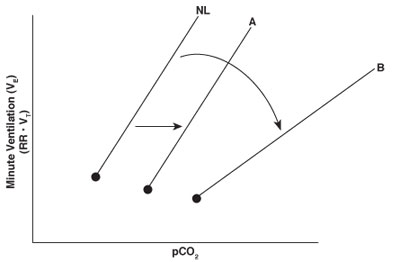

The central respiratory center is primarily located in the medulla and rapidly responds to changes in carbon dioxide. Changes in carbon dioxide concentration are among the most important determinants of respiratory drive from the medullary respiratory center. Carbon dioxide freely diffuses across the blood-brain barrier, resulting in an increase in H+ and a decrease in pH in the cerebral spinal fluid. The decrease in pH is accompanied by an increase in neural output from the respiratory center and in minute ventilation. Minute ventilation typically increases linearly with rises in PCO2.

The normal response to increases in carbon dioxide is noted by the line designated NL in the CO2 ventilation response curve. In general, sedative drugs suppress the central respiratory center and reduce the ventilatory response to a given level of carbon dioxide. Doses of sedative drugs that do not cause complete loss of consciousness (e.g., low-dose morphine or midazolam) usually displace only the CO2 ventilation response curve to the right while maintaining the slope of the response (line A). Under deeper levels of sedation, however, the slope of the CO2 ventilation response curve decreases as well as shifts to the right (line B). This response may occur when combining sedative drugs or using any sedative that results in unconsciousness. A decreased slope indicates less of an increase in minute ventilation for any given rise in carbon dioxide, a situation that may lead to severe hypercapnia or hypoxemia.

Clinical Implications

Drug selection and dosing

Be aware of the potential airway and respiratory depressive effects of medications used during sedation, titrate slowly and evaluate for response to help mitigate risks.

Monitoring

Careful monitoring of respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and end-tidal CO2 is essential during sedation to anticipate, detect, and manage upper airway obstruction or respiratory depression. Monitoring requirements differ according to depth of sedation achieved by the patient during procedural sedation.

Airway Management

Readiness to perform airway interventions, such as repositioning, suctioning, chin lift/jaw thrust, or insertion of airway adjuncts is necessary to ensure a prompt response to and reversal of adverse airway events.

References

American Society of Anesthesiologists. (2018). Practice guidelines for moderate procedural sedation and analgesia 2018: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Dental Association, American Society of Dentist Anesthesiologists, and Society of Interventional Radiology. Anesthesiology, 128(3), 437-479. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002043

Jonkman, A. H., de Vries, H. J., & Heunks, L. M. A. (2020). Physiology of the respiratory drive in ICU patients: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Critical Care, 24, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2776-z