The last 18 months have been a struggle for 6-year-old Cade Moureau and his family.

The child from Cottage Grove, Wisconsin, was diagnosed shortly after birth with Prader-Willi Syndrome, which is caused by microdeletions in the fifteenth chromosome. Cade, who is now a first grader, has a multitude of medical concerns, according his mother Katie Moureau.

Cade sees specialists at health systems throughout Wisconsin and as far away as Florida, she said. His condition causes lack of muscle tone, reduced hormone production, sleep apnea and waves of uncontrollable hunger, among other symptoms.

Additionally, his condition makes him more susceptible to illness, Katie said.

“In the last three years it seems he has been sick with something every year,” she said.

This led Katie to enroll Cade in a new study conducted by researchers at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health. Researchers are working with school districts in the state to develop a system of effective testing to help students with medical complexities, like Cade, return to in-person school safely.

The study, led by Ryan Coller, MD, MPH, assistant professor of pediatrics, and Greg DeMuri, MD, professor of pediatrics, is funded by a $2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Their study, “ReSET: Restarting safe education and testing for children with medical complexity,” is part of the NIH’s RADx-Up program, which aims to better understand COVID-19 testing patterns among underserved and vulnerable pediatric populations, strengthen the data on disparities in infection rates, disease progression and outcomes, and develop strategies to reduce disparities in COVID-19 testing. UW–Madison is one of 10 institutions in the nation to receive an NIH award through the RADx-UP program.

The study will test three approaches: establishing the feasibility of home and school-based COVID-19 testing strategies for children with medical complexities, identifying which factors lead parents of children living with medical complexity to opt for in-person school, and establishing recommendations to facilitate safe school attendance for this pediatric population, according to Coller.

Students with medical conditions that require special care often face inherently higher COVID-19 risks in school settings, but being in school buildings also allows direct access to specially trained experts who may provide therapy and educational services that are more feasible to deliver in person, he said.

“Parents are doing the best they can with their children at home, but these students in particular learn better when they have the specially trained staff with them daily,” Coller said.

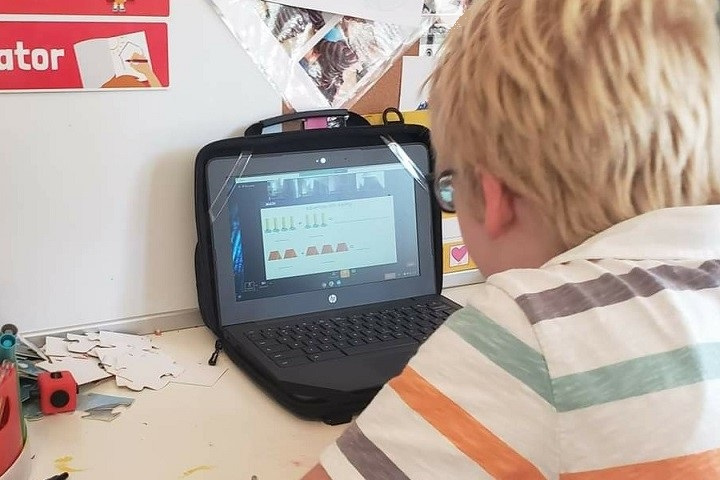

Indeed, the pandemic has been difficult on Katie and Cade as they navigate school from home, she said.

They have an assistant who comes to their home to help, but the teachers in Cade’s school district still need to communicate virtually through a tablet computer. This affects how his physical, occupational and speech therapy sessions are approached, she said, and some things do not translate well through a screen.

“Sometimes they can’t see him well when his doing physical therapy or they can’t hear quite right during speech therapy,” Katie said. “He’s missing the hands-on experts.”

More critically, Cade is not getting to see other students, she said.

“I can teach him academically, and he can carry on a conversation well with an adult, but he needs the socialization,” Katie said. “I worry about him socially and emotionally.”

Joining the study was important because it allowed Cade and his older brother, 12, to be tested for COVID-19 twice a week.

“Absolutely we were excited to join the study; we go nowhere now,” Katie said. “Ultimately, we want to make sure that he is safe, and so [if he tests positive for COVID-19] we can catch it and take action early.”

#####

Media Inquiries:

Andrew Hellpap

608-225-5024

ahellpap@uwhealth.org