Most American adults know what cholesterol is and why their doctors keep track of their “numbers”: high levels are frequently associated with heart disease. However, far fewer adults, including parents of small children, are aware of the importance of cholesterol screening for children. In 2015, Amy Peterson, MD, associate professor, Cardiology, and Kathleen DeSantes, MD, clinical associate professor*, General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, wondered if UW Health cholesterol screening rates had improved.

“Dr. DeSantes and I were discussing all the efforts the UW Health team had made to make cholesterol screening easier,” said Peterson, “and we wondered if they had resulted in increased screening rates.”

Through their initial investigations, they began to see that differences in pediatric cholesterol screening knowledge and attitudes, and consequently in clinical practice, existed among physicians. They began to suspect it was possible that pediatric cholesterol screening rates differed across specialties. This concerned them, as they were both involved in identifying and treating pediatric cholesterol disorders, particularly familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), an autosomal dominant disorder of excessive low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. People with FH have a six to 20 times greater chance of developing premature cardiovascular disease, or CVD. Early identification of the disorder in childhood allows for early treatment—and delay of atherosclerosis and early CVD. Peterson and DeSantes knew that early universal screening might be the only way to identify most FH in children.

“It’s not our goal to screen children in order to give them a little pill instead of encouraging healthy nutrition and exercise for elevated cholesterol,” said Peterson. “Screening is essential for us to identify cases of FH as early as possible, before the vascular effects begin. FH isn’t caused by diet—even children from vegan families, who run marathons, can have FH and need medication to lower their cholesterol. It’s a genetic trait passed down through families, so early identification and treatment are crucial.”

To investigate this question, Peterson and DeSantes recruited a group of University of Wisconsin (UW) clinician researchers and others to develop a research project examining rates of pediatric cholesterol screening across several specialties. The seven-member research team represented four specialties within the UW institution. Joining Peterson and DeSantes were Ann Dodge, NP, a nurse practitioner in Pediatric Cardiology; Xiao Zhang, PhD, an associate researcher also in Pediatric Cardiology; Megan Moreno, MD, MSEd, MPH, professor and division chief in General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine; Magnolia Larson, DO, associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health; and Jens Eickhoff, a scientist in Biostatistics and Medical Informatics.

The research team collected electronic health records, or EHR, data for pediatric patients aged nine to 12 years with a health maintenance (i.e., well child) visit to any health care provider in the institution between 1/1/2010 and 12/31/2019. There were 36,756 eligible pediatric care visits during the 10-year period. The team created filter parameters that selected patients with at least one well child visit and a completed full lipid panel screen in the previous three years. The screening order could originate from any type of clinical encounter; the specialty of each patient’s physician would be recorded.

Researchers found that 57.8% of the eligible patients had an order for a cholesterol screening placed at least once in the 10-year period. Order rates were highest among pediatricians, at 79.6%, followed by internists at 63%, and family physicians at 48.4%. On a per clinician basis, most pediatricians had an order placement rate, or OPR, of over 80%, while most family physicians had OPRs between 40 and 60%. Pediatricians’ OPRs were also placed for younger patients than those of family medicine physician OPRs: about 13 years of age compared to 15 years.

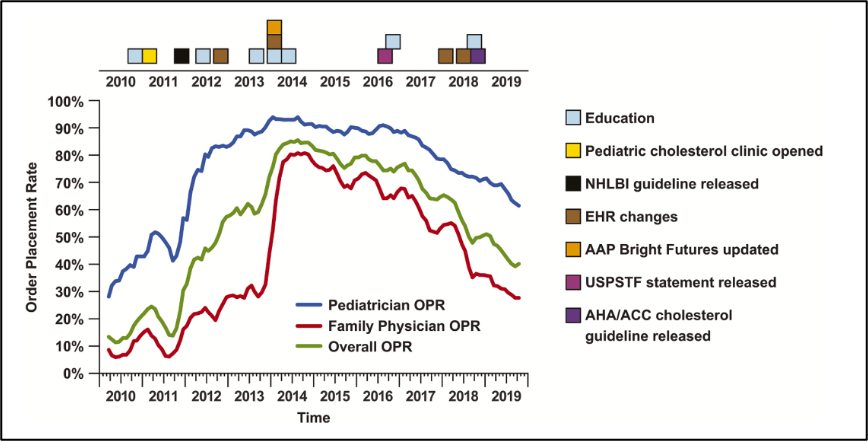

The team’s statistical analysis revealed an upward trend in pediatric cholesterol screening from 2011, a peak in 2014, and a subsequent decline in 2019 that was similar among pediatricians and family clinicians. The screening rate changes correlated closely with a series of health interventions, including four major national guidance releases that addressed pediatric cholesterol screening, in addition to educational initiatives, and modifications in the EHR system at UW Health.

In 2011, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) recommended universal cholesterol screening, which correlated to substantial increases in pediatric screening in both pediatrics and family medicine. Educational workshops, lectures, and EHR modifications that made lipid screen orders easier in 2012 and 2014 also correlated with increases in screening in pediatrics and family medicine. The American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) “Bright Futures” initiative in 2014 included universal screening recommendations.

In 2016, the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) did not recommend universal screening, instead giving it a neutral “I” rating, for “insufficient evidence.” In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology addressed pediatric cholesterol screening for the first time, giving it a “2B” recommendation, stating, “evidence is unclear.” Rates of pediatric screening have declined from 2014 and continue to decline, correlating with these national guidance releases and lack of uniform recommendations. Pediatricians follow NHLBI and AAP guidance, while family medicine follows USPSTF recommendations. What was of greatest concern to the research team was that national guidance releases from various sources were not consistent, at times even conflicting.

The research team also developed a Knowledge, Attitude and Practice survey for clinicians across specialties. The survey, disseminated to UW Health pediatricians and family medicine physicians, asked participants to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with 14 statements about pediatric cholesterol screening. Pediatricians showed greater knowledge, more positive attitudes, and a greater likelihood to screen than family medicine physicians. These differences seemed to suggest that conflicting national guidelines may have contributed to the decline in screening rates during the 10 years of the study—and into the current day.

The results of this study were concerning to the research team, revealing that clinicians from pediatrics and family medicine used different lipid screening guidelines. The outcome has been substantially different screening rates. The same population of children could be treated differently depending on their primary care physician’s specialty and source of guidance.

According to Larson, a member of the research team, the study demonstrated that the differing rates of cholesterol screening are most likely due to the different recommendations of medical guidance groups. “Physician education and improvements in EHR tools can improve screening rates, even if conflict remains in recommendations from national organizations,” added Larson.

Moreno, also of the research team, addressed possible paths forward. “This study suggests that next steps could include meeting with our family medicine colleagues to discuss these findings. There may be collaborative strategies that could ensure our UW Health pediatrics patients receive consistent and high-quality care regardless of whether their primary care provider is a pediatrician or a family medicine physician.”

The team’s completed project, including the clinicians’ survey and statistical analyses of 10 years of pediatric cholesterol screening order data, resulted in two journal publications in 2021. “Differences in pediatric cholesterol screening rates between family physicians and pediatricians correlate with conflicting guidelines” appeared online in Preventive Medicine in July 2021. “Practices and attitudes regarding pediatric cholesterol screening recommendations differ between pediatricians and family medicine clinicians” appeared online in Pediatric Cardiology in November 2021.

*Kathleen DeSantes retired in October 2021.