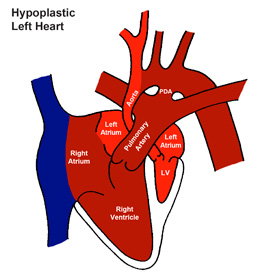

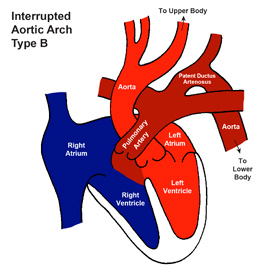

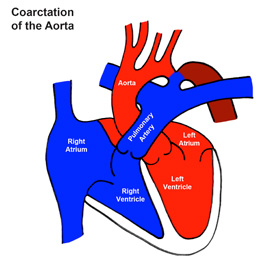

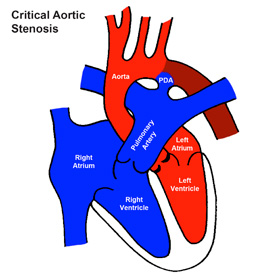

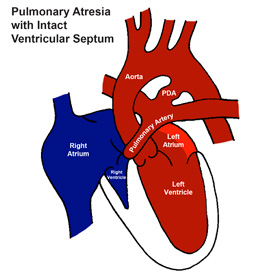

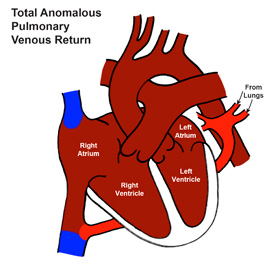

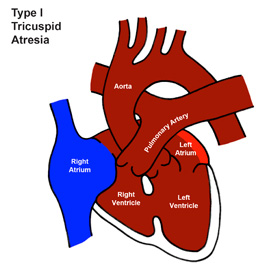

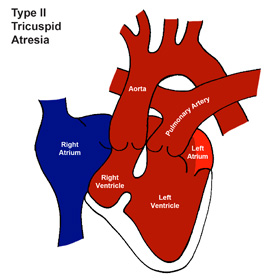

The following diagrams demonstrate some of the heart defects in which a child may appear well in the first day or two after birth, only to become ill when the ductus arteriosus closes. The common thread in these lesions is that the ductus provides a significant amount of blood to either the body or the lungs.

There are a number of different types of heart problems that may be missed in the blind spot.

The heart problems in which the right heart helps to supply body with blood because of a problem on the left side of the heart are those most commonly missed. These defects include, but are not limited to hypoplastic left heart syndrome, critical aortic stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and interrupted aortic arch. In all of these problems, there is something that prevents the left heart from delivering blood from the lungs to the body.

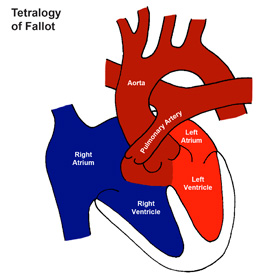

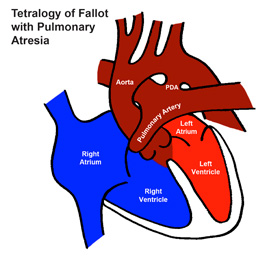

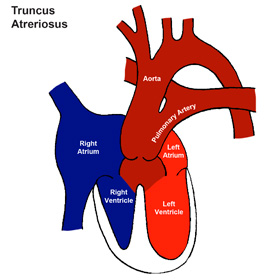

The heart problems in which the left heart helps to supply the lungs with blood because of a problem on the right side of the heart are occasionally associated with oxygen saturations which are low enough to cause visible cyanosis. These defects include, but are not limited to tricuspid atresia, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum, pulmonary atresia with VSD, tetralogy of Fallot, and truncus arteriosus.

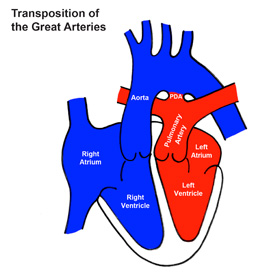

Significant cyanosis is also seen when then blood vessels to heart and lungs connect with the wrong ventricles. In transposition of the great arteries, the right heart pumps blood into the aorta and the left heart pumps blood into the pulmonary artery. If an associated ventricular septal defect is present, the degree of cyanosis may not be low enough to be visible.

In a condition known as total anomalous pulmonary venous return, all of the blood returning from the lungs enters the right heart and joins with the blood returning from the body. These babies may also appear well for a short period of time before becoming very ill.

Many of the blind spot heart defects have both an obstruction to blood flow and a hole in the heart. When there is an isolated and/or less severe obstruction of blood flow (aortic or pulmonary stenosis) or an isolated hole in the heart (ventricular septal defect), the oxygen saturations will likely be normal. Fortunately, in these conditions, there will usually be a heart murmur of other sign on physical examination.

Hypoplastic Heart Syndrome (HLHS) |

Interrupted Aortic Arch (IAA) |

Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) |

Critical Aortic Stenosis (Critical AS) |

Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) |

Tetralogy of Fallot with Pulmonary Atresia (ToF/PA) |

Transposition of the Great Arteries (TGA) |

Truncus Arteriosus (Truncus) |

Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum (PA/IVS) |

Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return (TAPVR) |

Tricuspid Atresia (TA) – Type I |

Tricuspid Atresia (TA) – Type II |

Missed Diagnoses

Congenital heart disease is the most common serious birth defect and over the last generation, the outlook for children with congenital heart defects has changed dramatically. With advances in treatment for congenital heart disease, some form of therapy is available for nearly all types of congenital heart disease. Although it would be more accurate to think of many of these children as being treated rather than being cured, many children with even the most severe forms of congenital heart disease will live into adulthood. However, if a babies dies or becomes critically ill before their heart disease is recognized, these advances are or no benefit to them.

Over time, the frequency of a missed diagnosis of congenital heart defect has decreased in large part due to advances in prenatal diagnosis. Despite these improvements, some children with critical congenital heart disease still missed until they become ill. Although more recent studies suggest a decrease in the rate of missed diagnosis.

In data published by Ng and Hokanson in 2010, approximately 1 in 25,000 babies born in Wisconsin between 2002 and 2006 died at home or in an emergency room or were readmitted to a hospital at less than two weeks of age due to unrecognized critical congenital heart disease. In this study 1in 40,000 babies died due to a missed diagnosis of missed congenital heart disease.

A study by Chang, Gurvitz, and Rodriguez of missed congenital heart disease in California from 2000-2004 suggested that up to 30 children a year died of missed or late diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease. This suggests a rate of death due to a missed diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease of approximately 1 in 20,000 births.

A review of missed congenital heart disease in 670,245 births in New Jersey from 1999 to 2004 by Aamir, Kruse, and Ezeakudo suggested a delayed diagnosis of critical congenital heart in 1 in 14,000 births.

A Swedish study published in 2006 by Mellander and Sunnegardh of 351,843 births between 1993 and 2001 showed a missed diagnosis of congenital heart disease in approximately 1:7,000 babies. This study also showed a disturbing trend toward an increase in the number of missed diagnoses as time went on as postpartum hospital stays decreased.

Although these studies defined congenital heart disease and the timing of a missed diagnosis differently, a missed diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease probably occurs in somewhere around 1 in 15,000 births. Unfortunately, approximately half of these babies will die before their heart disease is identified.